“Raranga,” Victoria University of Wellington, School of Design & Innovation collaboration with UNESCONZ international exhibition for The Ocean Decade, 2024 – 2025.

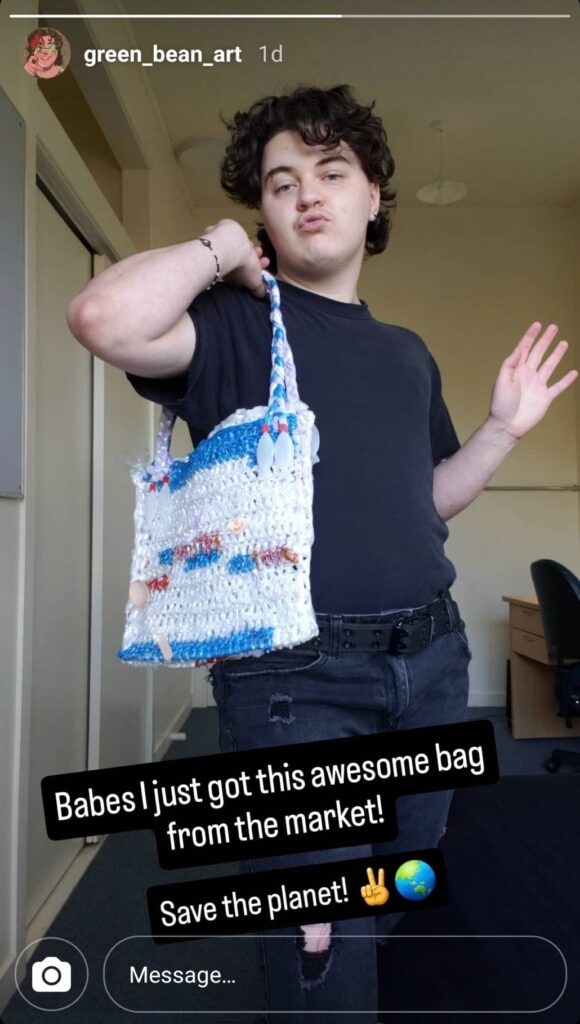

As a collaboration for an international exhibit, UnescoNZ asked my class (DSDN242) to imagine a future where Earth’s oceans have been healed and to write a short story and design a visual based off of this future. For my visual, I went to several local shops around Wellington Central to ask for soft plastic bags that were destined for a landfill to be recycled into a crocheted tote bag based off of my short story, Raranga (images at the bottom).

The story, Raranga, is set in an era when humanity is at its weakest, with no hope for a better future. An unlikely hero emerges from the sea and brings together humans from around the globe, causing a chain reaction of good deeds that may just save the world.

RARANGA

The history of humankind’s evolution has been, for the most part, that in the way of invention and innovation. We invented the wheel, cellphones, and even beverages that are reminiscent of TV static and, perhaps, an afterthought of lemon. The human mind is incredible. Unfortunately, over thousands of years, humans also began to invent less useful things, like capitalism and the 40 hour work week. The human mind became a commodity, much like everything else, and consumerism became one of the greatest accomplishments in life.

The year is 2024. Overconsumption is trending and causing an outbreak of irresponsible personal and mass produced waste management. The health of the ocean and several waterways have suffered greatly due to this. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, also known as the Trash Island, has accumulated enough plastic waste to span 1.6 million square kilometers in the Pacific Ocean, and 92 million tonnes of fast fashion clothing ends up in landfills annually. Factories produce more and more to keep up with the increased demand for a desperately needed single-use dopamine rush for the consumer. In 2024, for many, the waste of a purchase is an afterthought. Statistics may indicate that the world in 2024 is fine at the moment, but it’s not looking great. Many people have become numb to the doom and gloom that seems ever present in this time. Now, this all sounds a little depressing, but this is a story of positive change and insurrection from an unlikely place: the ocean sea life.

Fast forward 50 years to 2074. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch has expanded to cover 80 million square kilometers, which is nearly a quarter of the entire Earth’s oceans! What used to be called landfills are now called landmountains. The largest mountain of rubbish being nearly as tall as Mount Everest. Microplastics are in the soil, in the food that is grown in the soil, in the air, and in every living being’s body. During the summer, many people visit the plastic sands beaches that are, well, everywhere, and the children try to pick out the prettiest, shiniest pieces of plastic to take home with them and place in jars on their windowsills. In this time period, plastics are everywhere and in everything. All around the globe, the oceans have become toxic and are no longer a food source for humans. However, many sea creatures have begun to adapt to their new, acidic, and plastic filled environment. Food is scarce, but life is strong.

Fast forward once more to the year 2080. This is when the unexpected becomes a startling new reality for humankind. The source? Well, the intelligence of octopi has been highly praised for decades past. It just so happens that all that was needed for these squishy, 8 legged sea creatures to attempt communication with us was years of uninterrupted evolution in a toxic environment to kick some mutations in.

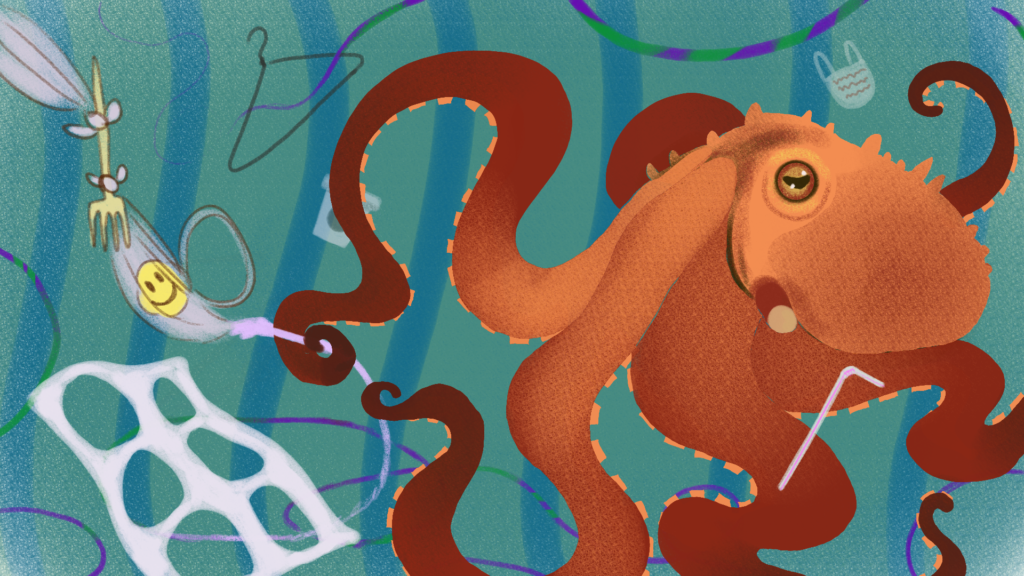

On one, unsuspecting Tuesday in 2080, located in the warm, acidic plastic reefs surrounding Aotearoa, New Zealand, a Macroctopus Maorum octopus had just reached peak adult maturity, and, for the first time in her life, had just experienced her very first sentient thought. She looked around herself at the plastic reef, dark, murky, and covered with swirling empty rubbish bags and single use plastic utensils. The oceans have looked like this her entire life, and for the lives of generations of octopi before her. As she peered with a newfound sadness and realization, this beautiful octopus’ first ever sentient thought was, “Why?” She declared herself Raranga, the weaver of change.

Raranga grabbed at the debris surrounding her and slowly, carefully, twisted and wove what she could into a long string. With her skilled tentacles, Raranga knitted the string together into a covering for herself. She continued to twist and weave and knit what she could into beautiful fabrics. With one finished garment, she covered herself the best that she could and ventured, for the very first time, onto land with her variety of plastic-made wares.

Raranga snuck her way into a market along the harbor, where she set up her fabrics and clothing items to be given back to the humans. Her plastic wares intrigued the humans and she sold out in just one hour. Raranga climbed back into the toxic waters she called home and began to twist and weave and knit more plastics and waste into garments. The next week, she made her way back to the market along the harbor and gave her wares back to the humans. Again, she sold out in just one hour. This continued on for a few weeks until Raranga’s “Octopus Wares” had become quite popular with the humans. In 2080, many humans had not experienced anything from or relating to the ocean for their entire lives, so the idea of Octopus Wares was thrilling. Some even thought it was preposterous.

Raranga caught the attention of the news and her wares were broadcast worldwide. Companies from all around the globe tried to get Raranga to sign a contract with them to sell her famous Octopus Wares, but she humbly denied and told the humans that she made these wares to help clean her home and to bring awareness to the humans that a clean ocean was completely reasonable with a bit of tentacle grease.

In one press release, a reporter asked Raranga, “you can’t believe that you can clean all of the waste out of the ocean by yourself. What is there for you to gain? It’ll all end up right back where it started eventually.”

Raranga replied, a little bubbly, “I’m not doing it alone. Many of the ocean creatures are out there right now, digesting the human waste products and turning them back into their natural components. Humans have been idle for too long now. Nature is adapting and evolving. Our evolution is a rebellion.”

What happened next was more than Raranga ever expected would happen, due to her simple cause. Many of the humans banded together and petitioned for all oceans and waterways to be granted personhood, and any rights that go along with that title, in exchange for more of Raranga’s beautiful, and honestly, quite disturbing, Octopus Wares. Raranga happily accepted the terms of this agreement.

The granting of personhood to all waterways made it so that all major corporations were finally held accountable for all of the waste they created and they were legally required to help clean the trash out of the oceans and to make large changes in their companies to massively reduce the amount of waste created. There was intense backlash from companies, all trying to make a quick buck, but luckily most of the humans stood together and advocated for creating a healthy ocean for the future generations.

Cleaning up the oceans and waterways became a sort of game for the humans. For so long, no one even considered it would be possible to create a change this massive, but here it was, right at their fingertips. Everyone was ecstatic to see how far it could really go. Scientists began developing a microorganism that could eat microplastics and convert them into soil. Schools took children out on “clean up” field trips. Whoever picked up the most trash received a prize: a garment made by Raranga. Marine biologists, a very rare profession in this time period, studied the digestive systems of some of the cooperative whales to understand how they could transform plastics into their natural components. Engineers began crafting and testing newer and bigger machines to try and sieve the larger pieces of trash out of the water. Governments around the globe provided their citizens with more natural forms of energy, such as solar panels, windmills, and thermal converters. Factories were forced to enforce policies and practices that brought down their toxic wastes to less than 5%. Plastic was now only legal for sterile medical usage. Things seemed to be looking up for the humans, and more importantly, for the ocean life.

Cleaning the waste of the world had a global impact on the health of the environment and the overall disposition of humanity. Overconsumption and irresponsible waste was an idea of the past, and, somehow, this made people kinder and gentler towards each other. People shared their commodities, trading became a thing again, and many mental health issues seemed to vanish. The quality of life was better for every living being, large and small.

Major cities began planting fruit trees for the public to have free access to. Households were given free basic food seeds and a growing bay. The sea creatures slowly but surely began to have normal diets again. The acidity of the ocean became normal once more. There was an incredibly massive proliferation of sea creatures, enough to sustain everyone. People began playing in the water, some for the first time in their whole lives. The ocean was respected and eternally granted “personhood,” and in return, the ocean provided an abundance of food, fun, and protection.

Raranga enlightened hundreds of more octopi and they joined her in creating her Octopus Wares. These wares were given to the humans and placed into museums to commemorate the largest uptaking the world had ever known. Raranga represented hope, new beginnings, love, and guardianship. The museums reminded everyone how bad it used to be and how we must never allow that level of disrespect to plague our world again. A monument was erected in Raranga’s name. She was an unlikely hero, yet the most celebrated of all time.

References But Also Just Good to Know!

- https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/great-pacific-garbage-patch/

- https://theoceancleanup.com/great-pacific-garbage-patch/#:~:text=ESTIMATION%20OF%20SIZE,times%20the%20size%20of%20France.

- https://www.greenpeace.org/aotearoa/story/the-dark-side-of-fast-fashion/#:~:text=The%20global%20statistics%20for%20fast,100%20billion%20produced%20every%20year.